On August 2, 1985, a Lockheed L-1011 Tristar operated by Delta Air Lines crashed short of runway 17L (now 17C) at Dallas-Fort Worth Airport. The cause? Mother nature herself.

Delta 191

The flight was a scheduled service from Fort Lauderdale to Los Angeles with a stop in Dallas. What was seemingly a normal flight would turn deadly in seconds.

The flight crew was aware of potential isolated thunderstorms near the DFW airport and reviewed these weather reports beforehand. These storms were nothing out of the ordinary during this time of year and likely did not raise major concerns in the pilots. However, pilots are always trained to never fly into a known thunderstorm, regardless of the circumstances.

On a short final to runway 17L (now 17C) at Dallas-Fort Worth International, it can be heard on the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR) that the captain notices some lightning in the cluster of clouds ahead of them on the approach. He says, "Lightning coming out of that one...Right ahead of us."

Despite this, they press on with the approach, penetrating a small cell with a microburst. The first officer (FO) is flying the aircraft, with the captain coaching him through this tricky flying scenario. He advises the FO to watch his airspeed, and as they begin to exit the microburst, the aircraft begins a descent that was never recovered from.

The captain called for a go-around, but the rate of descent and proximity to the ground meant it was already too late to recover. Delta 191 ended up touching down in a field over 6,000 feet short of the runway and, continuing for several hundred feet, struck a car on the highway (whose sole occupant died instantly) and eventually two water towers that brought the aircraft to rest. One hundred twenty-eight people died, with two of the deaths occurring more than 30 days after the accident.

What is a Microburst?

This weather phenomenon is very dangerous to aviation. There are two types of microbursts: wet and dry. Both have similar characteristics and pose a large threat to all aircraft types. If encountered at a low altitude on the final approach, they can be almost impossible to recover from.

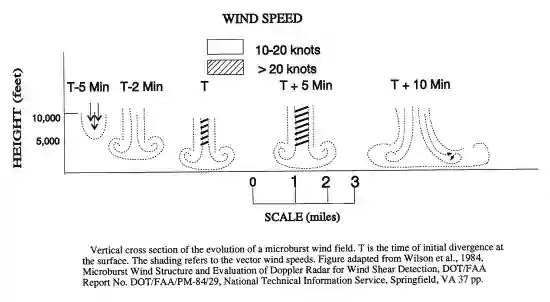

A microburst is a strong downdraft, usually 1-2 miles in diameter, associated with heavy rain and thunderstorms. They can last 5-15 minutes with downdrafts of up to 6,000 feet per minute.

They are usually recognized visually by falling precipitation in an upside-down mushroom shape. If the microburst is dry, it may be recognized by virga (moisture suspended in the atmosphere) or not at all. Noticing microbursts is very difficult unless seen from afar. If an aircraft enters a microburst, significant performance changes will be encountered that signify a microburst situation.

These performance changes are the result of something called "windshear."

What is Windshear?

Windshear is a term used to describe a sudden change in wind speed and/or direction. It is usually caused by rapidly changing pressures, with the strongest windshear being seen up at altitude. The jetstream, combined with steep pressure gradients, can create huge differences in wind speed at different altitudes up into the flight levels.

However, perhaps the most dangerous type of windshear is Low-Level Windshear. This is windshear that happens close to the ground and is usually either reported by aircraft on final approach or is detected by Low-Level Windshear Alert Systems on or around the airport. Modern aircraft flying today have windshear alert systems. These systems can detect and predict windshear, allowing the pilots to avoid it before encountering it.

But why is this so dangerous?

A sudden change in speed and direction can have a very significant impact on airspeed and the amount of lift an aircraft generates. Suppose an approach is being flown with a consistent strong headwind that suddenly changes to a tailwind 100 feet above the ground. In that case, the aircraft will experience a loss of lift and a drop in airspeed and begin to sink toward the ground if not corrected. This can result in a short or hard landing.

Even if there is no change in direction, a sudden shift in windspeed will have a similar or converse effect that can render an approach unstable. These changes will result in swift airspeed changes and variations in rate of descent. If any of these happen, pilots are trained to discontinue the approach and go around immediately. Windshear escape maneuvers are constantly prepared for in the airlines.

What We Can Learn

Aviation has come a long way since this accident. Now, there are much more accurate and advanced Low-Level Windshear Alert Systems, warning us about any microburst activity such as the cause of Delta 191. A better appreciation for thunderstorms and windshear/microburst escape training is the norm in airline and recurrent training.

Even in initial private pilot training, applicants must understand the characteristics of a microburst, where we might find them, and how to spot them. The same is the case for thunderstorms since the two seem to coincide. Applicants must learn and appreciate the change in performance characteristics of the aircraft to better prepare for an escape, should we ever inadvertently enter one.

Reassuringly, the dangers of this weather phenomenon are constantly reinforced throughout pilot training, however senior and experienced you are. Maneuvers to avoid and escape them are practiced repeatedly, with pilots not even needing to avoid them thanks to advanced weather prediction models and surface analysis products available to us today.

The great news is that we, as pilots, have so many resources available to us before and during the flight to help us spot any potential meteorological threats such as these, with modern technology assisting us greatly in avoiding them.

IndiGo Unveils Delhi–London Expansion and First A321XLR Launch » US Air Force to Launch New Experimental One-Way Attack Drone Unit » Pentagon Alarm: China’s ‘Tailless’ 6th-Gen Fighter Prototypes Are Already Airborne »

Comments (0)

Add Your Comment

SHARE

TAGS

INFORMATIONAL Delta Delta Air Lines Crash Air Crash Investigation Meteorology Thunderstorms DFW Lockheed L-1011 Texas Dallas-Fort Worth HistoryRECENTLY PUBLISHED

KAL858: The North Korean Bombing that Shocked the World

Among the 99 passengers boarding Korean Air Flight 858 on November 29, 1987, few could imagine their journey would end as one of aviation's darkest mysteries.

STORIES

READ MORE »

KAL858: The North Korean Bombing that Shocked the World

Among the 99 passengers boarding Korean Air Flight 858 on November 29, 1987, few could imagine their journey would end as one of aviation's darkest mysteries.

STORIES

READ MORE »

Ghost Networks: The Rise, Fall, and Revival of Fifth-Freedom Flights

Fifth-freedom flights — routes where an airline flies between two countries outside its home base — have always lived in aviation's twilight zone. We chart their rise, their near-disappearance, and the surprising markets where they still thrive today. Then we take you on board a special Seoul-Tokyo fifth-freedom flight to show how the experience stacks up against a typical regional carrier.

TRIP REPORTS

READ MORE »

Ghost Networks: The Rise, Fall, and Revival of Fifth-Freedom Flights

Fifth-freedom flights — routes where an airline flies between two countries outside its home base — have always lived in aviation's twilight zone. We chart their rise, their near-disappearance, and the surprising markets where they still thrive today. Then we take you on board a special Seoul-Tokyo fifth-freedom flight to show how the experience stacks up against a typical regional carrier.

TRIP REPORTS

READ MORE »

US Air Force to Launch New Experimental One-Way Attack Drone Unit

In a move that signals a tectonic shift in American airpower, the U.S. Air Force is preparing to stand up its first-ever experimental unit dedicated solely to "One-Way Attack" (OWA) drones.

NEWS

READ MORE »

US Air Force to Launch New Experimental One-Way Attack Drone Unit

In a move that signals a tectonic shift in American airpower, the U.S. Air Force is preparing to stand up its first-ever experimental unit dedicated solely to "One-Way Attack" (OWA) drones.

NEWS

READ MORE »