You have probably observed that most aircraft share common features: most notably round, oval windows. But did you know that there is a reason for this?

The world’s first commercial jet airliner, the de Havilland 106 Comet, was perhaps more well-known for its flaws than the jet age it ushered in. The first prototype flew in 1949 with development taking place in the United Kingdom by de Havilland.

At the time, it was the gold standard in quiet, comfortable travel, using pressurization to fly at higher altitudes faster and more comfortably. This led to an aircraft sought after by those wanting to see the world from a higher vantage point and in seats more luxurious than in most homes.

In 1952, the Comet was first introduced on scheduled passenger flights, which is where the trouble began. At that time, most aircraft flew at lower altitudes, presenting no need for them to be pressurized as they accumulated very little stress. The lack of key knowledge of pressurization effects on fuselages would prove to be deadly.

{{AD}

Why did Airplanes Have Square Windows?

It is important to note that most World War 2-era aircraft used square windows because they were easy to assemble. Flying at low altitudes did little to affect the windows and the fuselage at large, and thus de Havilland followed suit and used square windows on its Comet aircraft. Testing the windows suggested that there would be limited problems. This would prove to be wrong.

The DH106 Plane Crashes

Shortly after the first scheduled flight in the spring of 1952, on October 26, 1952, a Comet operated by BOAC suffered a failed takeoff in Rome and slid off the edge of the runway. Just eight months later, on May 2nd, 1953, a Comet experienced an in-flight break-up while ascending in stormy weather. There were no survivors.

According to the FAA, investigators concluded that the airplane's structure had failed due to overstress by either severe wind gusts or over-control of the airplane by the pilot while trying to navigate the storm.

The continual failure of the airplane's structure presented further problems almost immediately. In January of 1954, another BOAC flight departing Rome suffered a similar in-flight breakup while climbing, crash landing into the Mediterranean Sea and killing everyone on board.

The same exact problem happened again three months later in April of 1954. This time, a contracted flight through BOAC departing from Rome broke up while climbing, crashing into the Mediterranean Sea.

In response, investigators performed heavy fuselage testing on the Comet by using water tanks to simulate real flight cycles. After almost two thousand simulated tank cycles were performed on the fuselage, the fuselage failed at the corner of a forward escape window which, like all windows on the fuselage, was square. Evidently, the fuselage was very prone to fatigue and, thus, rupture. Yet, what de Havilland did not account for was how quickly stress would build up at the windows, which they believed had already been robustly tested.

As engineers now know, modern, oval windows allow stress from pressurization to flow unimpeded around the edges of the window. The Comet’s square windows “trapped” stress to the corners, producing buildup, which is what led to the damage. The added altitude led to significant pressure differences between the inside of the cabin and the outside of the plane, causing an expansion of the fuselage. Square windows only made the problem worse.

Importantly, the stress calculations de Havilland conducted on the windows when designing the aircraft were an "average" of stress levels in the region; they did not account for how much stress could build up at a specific part of the window. This led to inaccurate calculations, causing the potential for in-flight stress buildup to be overlooked.

After the third crash, the Comet never flew again. Since then, no airline has introduced a commercial airliner with square windows.

In 1958, oval windows were introduced on commercial aircraft, which has become an industry standard ever since. Stress buildup around windows has remained a minor factor in subsequent crashes as aircraft engineers look to perfect designs of other aircraft parts. Modern windows also contain additional protections, like layers of acrylic for protection from outside elements and a “bleed hole” to help keep air pressure relatively constant on board.

Big Wings, Bigger Job: How the Dreamlifter Keeps Boeing's Assembly Lines Moving » Korean Air Orders A350F Freighter » Delta to Launch Nonstop Flights to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia »

Comments (0)

Add Your Comment

SHARE

TAGS

INFORMATIONAL Window Engineering Round Comet De Havilland De Havillan Comet Aerospace Engineering Aeronautical Engineering Aviation Aviation History History Air Crash AccidentRECENTLY PUBLISHED

Big Wings, Bigger Job: How the Dreamlifter Keeps Boeing's Assembly Lines Moving

In modern aircraft manufacturing, it's common for different components to be built in factories scattered across the globe. Bringing these parts together for final assembly can pose significant logistical challenges, especially when the factories are separated by thousands of miles. Enter the Boeing Dreamlifter: a fleet of four specially-modified Boeing 747s designed to solve this very problem.

INFORMATIONAL

READ MORE »

Big Wings, Bigger Job: How the Dreamlifter Keeps Boeing's Assembly Lines Moving

In modern aircraft manufacturing, it's common for different components to be built in factories scattered across the globe. Bringing these parts together for final assembly can pose significant logistical challenges, especially when the factories are separated by thousands of miles. Enter the Boeing Dreamlifter: a fleet of four specially-modified Boeing 747s designed to solve this very problem.

INFORMATIONAL

READ MORE »

The Next Big Upgrade in Air Travel Might Be Your Window Shade

While most cabin refurbishments focus on plush seats and mood lighting, one Florida company believes the next big upgrade lies in something passengers barely notice: the window shade.

STORIES

READ MORE »

The Next Big Upgrade in Air Travel Might Be Your Window Shade

While most cabin refurbishments focus on plush seats and mood lighting, one Florida company believes the next big upgrade lies in something passengers barely notice: the window shade.

STORIES

READ MORE »

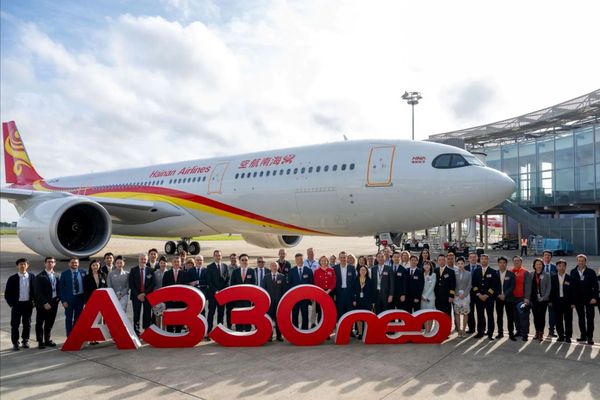

Hainan Airlines Takes Delivery of First A330-900neo

On October 31, Hainan Airlines received its first A330-900neo, marking the first delivery of this aircraft type to a Chinese carrier.

NEWS

READ MORE »

Hainan Airlines Takes Delivery of First A330-900neo

On October 31, Hainan Airlines received its first A330-900neo, marking the first delivery of this aircraft type to a Chinese carrier.

NEWS

READ MORE »