Whenever a major air incident occurs, authorities can determine the cause of the crash following a comprehensive investigation. However, the case of South African Airways Flight 295 is unique. Unfortunately, the exact cause of this tragedy continues to remain unknown. This is the mystery of the Helderberg.

Background

On November 28, 1987, South African Airways Flight 295 was preparing for departure from Taipei's Chiang Kai-shek International Airport in Taiwan (TPE). The flight was returning to Johannesburg, South Africa (JNB), with an intermediate stop in Mauritius (MRU).

The aircraft operating the flight was a seven-year-old Boeing 747-200BM Combi registered ZS-SAS. The plane was named Helderberg after the mountain in South Africa's Western Cape.

The 747-200BM is a "combi" aircraft, meaning it has a designated area for passengers and a small main deck cargo section in the rear. The aircraft has a large main deck cargo door that can load cargo.

On the day of Flight 295's departure, it was carrying 140 passengers from Taipei, mostly South Africans, Taiwanese, and Japanese citizens. Six cargo pallets were loaded into the main deck cargo section, with 104,000 pounds (47,174 kilograms) of baggage and cargo. While conducting a surprise inspection, a Taiwanese customs official did not find anything suspicious in the cargo manifest.

Tinus Jacobs, SAA's manager in Taiwan at the time, noted that the flight crew appeared relaxed and "happy to fly" and did not display any concerns about the cargo. The flight crew were very experienced individuals. Captain Dawid Jacobus Uys was a former South African Air Force Pilot with 13,843 hours of experience, over 3,800 of which were on the 747.

The rest of the cockpit crew were also rather seasoned on the 747. They were First Officer David Atwell (4,096 hours), Relief First Officer Geoffrey Birchall (4,555 hours), Flight Engineer Giuseppe Bellagarda (4,254 hours), and Relief Flight Engineer Alan Daniel (227 hours).

Spontaneous Tragedy

SAA Flight 295 departed Taipei at 10:23 p.m. local time for its first leg to Mauritius. The flight passed without issue until the aircraft neared Mauritius. As the crew prepared for the approach into Mauritius, it is believed that a fire developed in the main deck aft cargo hold. The crew contacted Mauritius Air Traffic Control and notified them they had begun descending to 14,000 feet (4,267 meters) following the fire being detected.

According to the smoke evacuation checklist, the aircraft should be depressurized, and two cabin doors should be opened. Specifically, the cabin doors that lead into the aft cargo section.

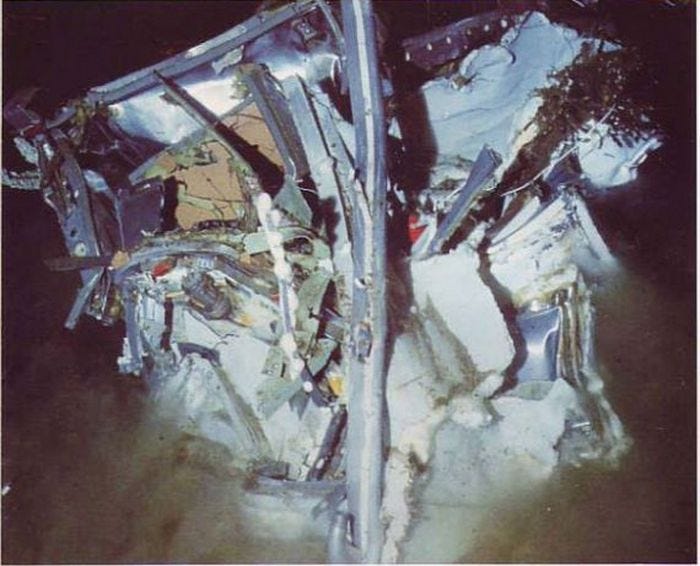

There is no evidence that any part of the checklist was followed; however, a crewmember might have gone into the cargo hold to fight the fire. The only evidence of this was a charred fire extinguisher recovered from the wreckage with molten metal on it.

The fire began destroying the aircraft's important electrical systems, resulting in a loss of communication and control of the 747. At 00:07 UTC (4:07 a.m. local time), the 747 broke apart mid-air. This was 19 minutes after Flight 295 had first called Mauritius ATC. The tail section broke off first because the fire in the aft cargo hold had burned this part of the aircraft. The plane crashed into the Indian Ocean about 154 miles (248 kilometers) from the airport. Everyone onboard perished.

ATC made repeated attempts to contact Flight 295 but to no avail. After communication was lost for 36 minutes, a formal emergency was declared. When Flight 295 last informed ATC of its position, the controllers incorrectly understood the position to be relative to the airport rather than its next waypoint (what was intended by the pilots). Flight 295 reported its position as 65 miles (105 kilometers). The 747 was 65 miles (105 kilometers) from waypoint "Xagal" and 145 miles (233 kilometers) from the airport.

This misunderstood report caused the naval search to be concentrated too close to Mauritius. The United States and French Navies operated in conjunction during the search. The first debris was located 12 hours after the plane impacted the water. It had all drifted considerably from the initial impact location. However, oil slicks and eight bodies showing signs of extreme trauma appeared in the water.

Investigation

Immediately following the crash, it was suspected that terrorism brought down the 747, given the sudden nature of the fire. Furthermore, South Africa had been the target of various terrorist attacks while under the apartheid government. However, no evidence of terrorist involvement was found in the investigation.

It was discovered that the front-right pallet located in the main deck cargo hold was the seat of the fire. The manifest said that this pallet was mostly comprised of computers in polystyrene packaging. While there have been various theories regarding how the fire started, the most recent one came in 2014. South African journalist Mark D. Young theorized that a short circuit in the onboard electronics may have started the fire.

A similar instance happened in 1998 with the Swissair Flight 111 incident, when a short circuit caused a fire onboard the MD-11, causing it to crash. This was the first incident involving the Combi variant of the Boeing 747. The investigation revealed that the 747 Combi's use of a "Class B" cargo hold did not provide enough fire protection to the passengers. This was confirmed in 1993 by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

South African Airways removed 747 Combi aircraft from its fleet after the incident. The FAA introduced new regulations in 1993 specifying that manual firefighting must not be the primary fire suppression in the main deck cargo hold. These new regulations banned larger cargo holds from being made on 747 Combi planes.

Furthermore, the regulations came with new standards that required weight increases. These made the 747 Combi less efficient and thus less desired by airlines. The "Combi" production of the 747 lasted through the -400 variant, with the last "Combi" plane being built in 2002. It was a 747-400M delivered to KLM.

NTSB: Maintenance Error Led to Citation CJ4 Gear Collapse in Baton Rouge » China Eastern Inaugurates New World's Longest Flight » Engine Failure Forces United 777 Emergency Landing, Starts Brush Fire at Dulles Airport »

Comments (0)

Add Your Comment

SHARE

TAGS

STORIES Boeing 747 South Africa South African Airways Crash Incident HistoryRECENTLY PUBLISHED

How Borders Shape Human Stories

The existence of borders can be seen through not only maps; they are also emotional markers that determine how an individual travels or moves, how an individual dreams, and what the individual considers to be their place in the world.

INFORMATIONAL

READ MORE »

How Borders Shape Human Stories

The existence of borders can be seen through not only maps; they are also emotional markers that determine how an individual travels or moves, how an individual dreams, and what the individual considers to be their place in the world.

INFORMATIONAL

READ MORE »

NTSB: Maintenance Error Led to Citation CJ4 Gear Collapse in Baton Rouge

NTSB has determined that improper installation of a critical landing gear component caused a Cessna Citation CJ4's right main landing gear to collapse during landing rollout in September 2025

NEWS

READ MORE »

NTSB: Maintenance Error Led to Citation CJ4 Gear Collapse in Baton Rouge

NTSB has determined that improper installation of a critical landing gear component caused a Cessna Citation CJ4's right main landing gear to collapse during landing rollout in September 2025

NEWS

READ MORE »

Austrian Airlines Abruptly Terminates Wet Lease with Braathens Regional Airlines

Austrian Airlines has abruptly terminated its wet lease agreement with Swedish regional carrier Braathens Regional Airways, effective immediately, marking a dramatic reversal in a partnership that was extended just months ago.

NEWS

READ MORE »

Austrian Airlines Abruptly Terminates Wet Lease with Braathens Regional Airlines

Austrian Airlines has abruptly terminated its wet lease agreement with Swedish regional carrier Braathens Regional Airways, effective immediately, marking a dramatic reversal in a partnership that was extended just months ago.

NEWS

READ MORE »